Formative assessment is often discussed in K-12 settings as a standard and expected part of curriculum delivery. In higher education, however, conversations about formative assessment have been somewhat more elusive. Traditionally, we rely on the high-stakes midterm, project, paper, final model which leaves little room for formative assessment that can foster growth.

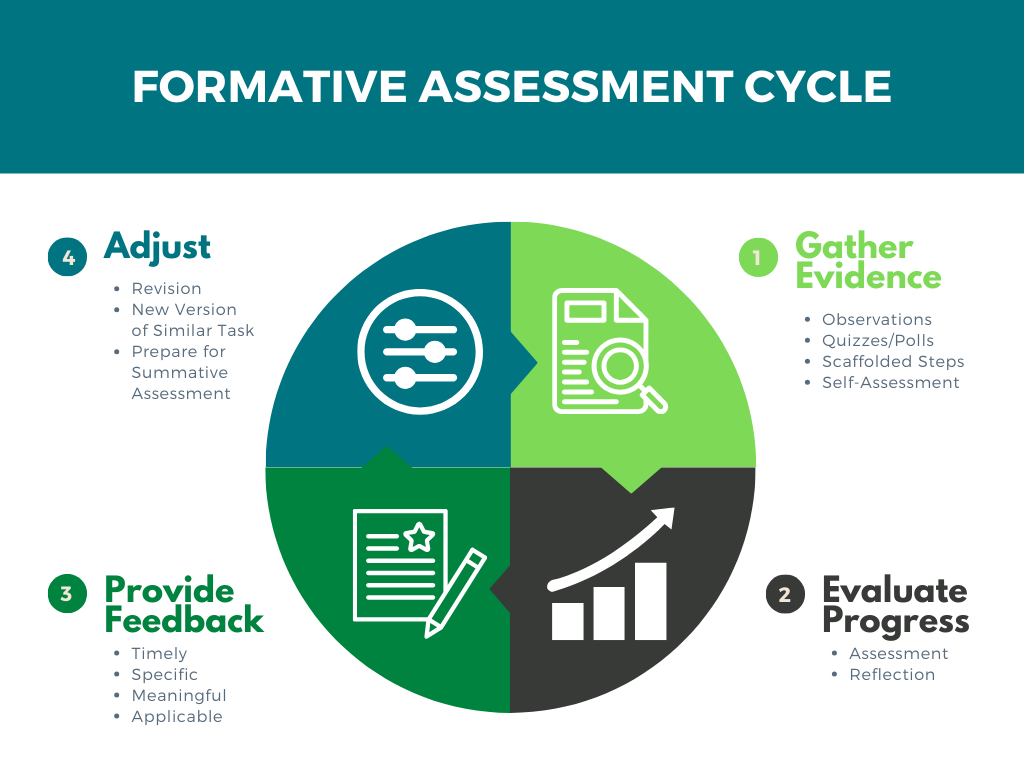

Using formative assessments is a valuable curriculum practice that allows faculty and students to monitor student progress toward completing larger, summative assessments and achieving the course’s learning objectives. But what makes formative assessment a valuable tool for academic progress?

Formative assessments are not just small assignments or what students are assigned for homework. Formative assessments typically reveal students’ academic strengths, but they can also draw our attention to students’ misconceptions or other areas where they may benefit from more reinforcements, scaffolding, or practice. Some students who use negative self-talk, for example, may believe or say they do not know anything about the course material; however, formative assessments can illustrate to students what they do know while also indicating specific areas where they may need help. Suppose a 6-question knowledge check reveals a student is proficient in 4 of 6 questions. In that case, the student may then be able to take the knowledge check assignment to tutoring or office hours and ask for specific guidance about those two questions they couldn’t answer on their own.

Formative assessments are typically low-stakes assignments that are sometimes ungraded, graded for completion rather than correctness, or graded overall with low point deductions for errors.

Most authentic learning includes errors and our assessment practices can easily recognize that by differentiating the way we evaluate formative assessments from summative assessments. The goal of formative assessment is continuous improvement, so failing students on a first or second attempt doesn’t make sense when the goal of formative assessment is to monitor progress rather than evaluate overall proficiency in course objectives.

Examples of formative assessments include in-class or online discussions; clicker questions or Kahoots; low-stakes group work; weekly quizzes; 1 minute reflections; digital polls or word clouds; essay drafts and small homework assignments. Ideally, students will complete one or two formative assessments in the first 10 days of a course and receive success-oriented feedback to give them a clearer picture of where they stand with the course content and also where to focus their study and practice efforts.

| Examples of Formative Assessments | ||

|---|---|---|

| Ungraded quiz, poll, or kahoot | Discussion or forum | essay or lesson plan draft |

| Outlines/timelines | Math practice | Collaborative Perusall |

| 1 minute paper | Concept map graphic organizer | Peer-teaching |

| Concept analogies (The _______ is like _________ because ____________.) | Based on this class session/module, create 1 multiple choice question and one discussion or illustration question | Surveys/self assessments |

Immediate, success-oriented feedback or feedback-driven metacognition (Agarwal & Bain, 2019) combined with formative assessments can pay off for students and instructors. In one study on the impact of immediate and delayed feedback on learning, the researchers discovered that when given immediate feedback, “students showed a significantly larger increase in performance than those who received delayed feedback” (Stenger, 2014). In another study on essay submission feedback, researchers discovered the least improvement from one formative assessment to the next when the feedback was only comprised of “praise, probes, grammar, referencing, and unclear comments” (Hattie et al, 2021, p. 6) . However, when students were given actionable, specific suggestions for the next steps in their writing, the researchers saw greater improvement from one draft to the next. Data gathered from formative assessments can benefit faculty, too. Formative assessments show us where to devote more time and where we can speed things up. Giving students more direct intervention in course content through formative assessments can result in student persistence toward face to face and online course completion (Ivankova & Stick, 2007; Burrus, Shaw, & Ferguson, 2013).

Typically, success-oriented feedback goes beyond quantitative scores. There are usually two pieces of qualitative feedback that first identify some strengths, including those that recognize students for submitting work on time, using excellent organizational skills, or demonstrating knowledge of past or future course content. Even if the student struggles with the particular content, when we recognize their habits or practices that are valuable to college success, we build student confidence and invite them to persist; we create narratives that indicate to students that they belong in college and have what it takes. Then, in an additional line or two, the feedback should also offer students tangible next steps that will help them correct or improve some aspect of the work they submitted. Most success-oriented feedback, when done effectively, can be short while also prompting students to take specific action.

Below are some examples of what immediate, success-orientated feedback for formative assessments may look like. The instructor focus for the examples below is to give specific, individualized action steps to individuals or groups. What have you tried? What do students respond to most?

| Instructor’s Feedback Goal | Type of Formative Assessment | Immediate, Success Oriented Feedback |

|---|---|---|

| Be specific | Two-problem math homework | Feedback to individual student: On both of the problems, you did a great job using the rule of thumb “what you do on one side of the equal sign, you do to the other” and it got you almost all the way to the end of the problem. Let’s look at this final part where you said “something went wrong”. That’s a good instinct. Let’s try (insert practice) and see if we can finish the problem and get the answer you want. |

| Be specific | In class math practice | Feedback to group: The picture you drew on the side helped me understand how your group thought about this problem. The representation of (insert concept) was effective; I had not thought about that. It looks like this part of the illustration, though, is missing from your written explanation. |

| Be specific | Draft essay | Feedback to individual student: You’ve selected a strong topic that a lot of us are interested in. Because you’re working with cause and effect, consider brainstorming the prompt “what is the effect of X on Y?” For example… |

| Be specific | Concept map | Feedback to individual student or group: Your concept map of “states of matter” really effectively documents and establishes relationships between solids and liquids. The map is missing gasses entirely. Where would you add that in? |

| Be specific | Lesson plan | Feedback to individual student: The narrative explanation of the body in your lesson helps me visualize exactly what your instructional goals are. Your lesson plan includes objectives, assessments, and standards, but the assessment does not evaluate the objective you’ve written. That objective would evaluate… |

When I took the road test for my license at age 15, the DMV employee who tested me failed me with no explanation. There were no notes, no discussion, and no suggestions for what I could practice or work on before I returned to try again. When I took it a second time with a different instructor, she asked me how well I could parallel park and, filled with anxiety, I said, “not well; I have practiced, but I live in the country and no one parallel parks there.” And she smiled and said, “you’re in luck. They just painted the parallel parking bars bright yellow and I wouldn’t want you to scratch them up on my watch. So let’s do a three-point-turn and we’ll skip the parallel parking today, but you should practice it more because you never know when you’ll need it, and you’ll get better at it over time. If there aren’t really places that require you to parallel park where you live, make your own practice space and try it out every now and then.”

I’m not sure if I should have skipped the parallel parking experience that day or if I should have stayed longer in a slow-turning lane while she rolled down the window and exuberantly spoke to her friend in the car beside us, but I did learn something valuable from her that has guided a lot of my teaching. The first instructor evaluated my performance more like it was a major summative assessment where you either knew it all and passed or you didn’t and failed. The second instructor included me in evaluating my work and preparation for the test and she seemed to view the road test as more of a formative assessment than a high-stakes summative assessment. I didn’t get a perfect score but I did pass and she gave me some immediate, success-oriented feedback so I could continue working on some aspects of my driving. Because of that, she helped me discover I wasn’t terrible at driving like the first instructor made me believe, but that I had successfully completed the majority of the test and also had room for growth.

This isn’t to say summative assessments should not be used or that parallel parking should be removed from the road test, but rather to say when there is a clear opportunity for guided growth you never know how long it will impact the learning life of students. I went on to successfully parallel park many times in Washington DC, Boston, and Charleston. I’m certain that accomplishment is owed to going home and practicing that day instead of giving up.

References

Agarwal, P. K., & Bain, P. M. (2019). Powerful teaching: Unleash the science of learning. Jossey-Bass.

Burrus, S., Shaw, M., & Ferguson, K. (2013, December). An analysis of the relationship between feedback types and student retention in online higher education. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/259234855_An_analysis_of_the_relationship_between_feedback_types_and_student_retention_in_online_higher_education

Chiappetta, E. (2022, January 4). Using positive feedback in math classrooms. Edutopia. https://www.edutopia.org/article/using-positive-feedback-math-classrooms/

Dmoshinskaia, N., Gijlers, H., & Jong, T. de. (2021, September 27). Giving feedback on peers’ concept maps as a learning experience: Does quality of reviewed concept maps matter? – learning environments research. SpringerLink. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s10984-021-09389-4

Formative and summative assessments. Poorvu Center for Teaching and Learning. (2021, June 30). https://poorvucenter.yale.edu/Formative-Summative-Assessments

Hart, C. (2012). Factors Associated With Student Persistence in an Online Program of Study: A Review of the Literature. Journal of Interactive Online Learning , 11(1), 19–42. https://doi.org/https://www.ncolr.org/jiol/issues/pdf/11.1.2.pdf

Hattie J, Crivelli J, Van Gompel K, West-Smith P and Wike K (2021) Feedback That Leads to Improvement in Student Essays: Testing the Hypothesis that “Where to Next” Feedback is Most Powerful. Front. Educ. 6:645758. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2021.645758

How to Parallel Park: 10 Super Easy Parallel Parking Steps (2012) Driving. Available at: https://driving-tests.org/beginner-drivers/how-to-parallel-park/ (Accessed: 15 September 2023).

Opitz, B., Ferdinand, N. K., & Mecklinger, A. (2011). Timing matters: the impact of immediate and delayed feedback on artificial language learning. Frontiers in human neuroscience, 5, 8. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnhum.2011.00008

Stenger, M. (2014) 5 research-based tips for providing students with meaningful feedback, Edutopia. Available at: https://www.edutopia.org/blog/tips-providing-students-meaningful-feedback-marianne-stenger (Accessed: 15 September 2023).

Thesis statements. The Writing Center • University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. (2021, April 14). https://writingcenter.unc.edu/tips-and-tools/thesis-statements/